Action replay

Learning from the mistake of others

Going over what went wrong can help us get things right. It might be an argument with a friend, a meeting at work, or a sequence on the sports field. Reflecting on how things played out in the past can teach us in the present so that we are better prepared for the future.

In recent months I have been looking into some of the theological trends in England in the mid to late 1600s. Although this work is unlikely to make it's way into my PhD, it has been enabling me to better understand the intellectual waters Stephen Charnock was swimming in as he was writing and preaching.

And here’s the thing. Learning about what happened in the hearts of one particular group of people nearly 400 years ago has provided a sobering lesson for me today. It’s a lesson that I am praying that I’ll never forget.

Common rejection

One of the circles that I have been looking at in my studies are a collection of thinkers known as the Cambridge Platonists. Although they were around in the seventeenth century, this group of scholars and ministers only picked up their name a couple of hundred years later when people started studying them. In fact, it's questionable how much they saw themselves as a group at all.

But what has caused people to lump the Cambridge Platonists together is that they were all people who rejected the good theology in which they were raised. And they all rejected it in a similar way.

Predestination pooh-pooh

One such person was a man called John Smith. Not the one of Victorian brewing fame, this John Smith was born in 1618 and went on to tutor at Queen’s College in Cambridge before dying from tuberculosis at the age of 34. Although he published no books in his lifetime, Smith did not pass away without leaving a legacy.

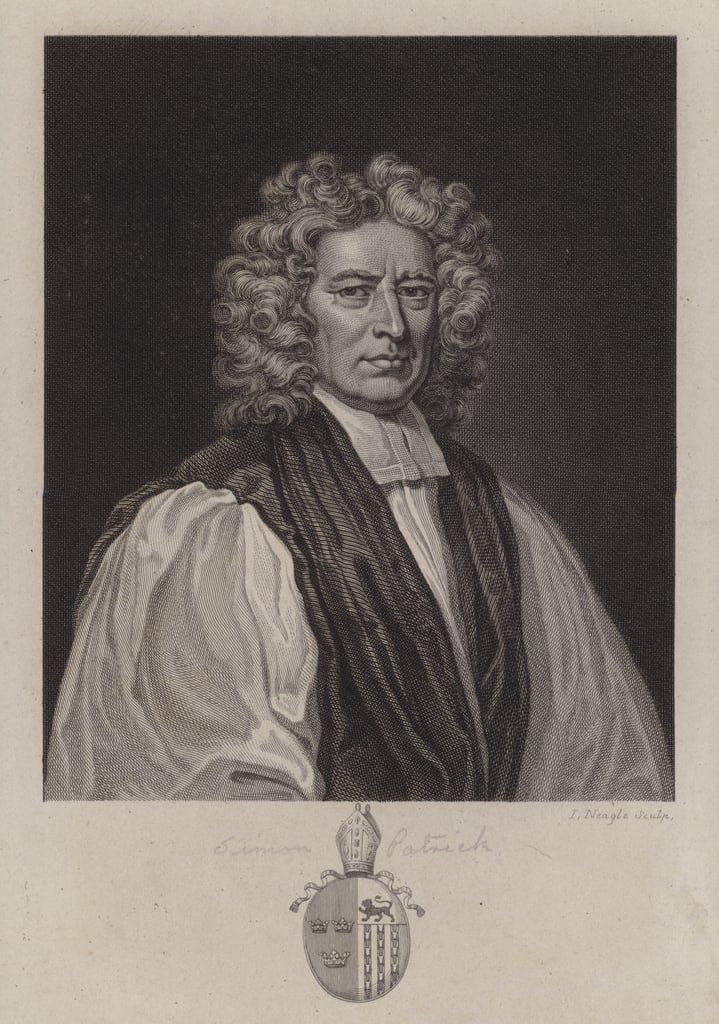

This is well illustrated by a story told later by someone called Simon Patrick, who had by then become one of the most influential bishops in the country. In his autobiography Patrick recounted a conversation which he had with Smith when Smith had been one of Patrick’s tutors at university. Patrick said that he and Smith were

discoursing together about the doctrine of absolute predestination; which I told him had always seemed to me very hard, and I could never answer the objections against it, but was advised by divines to silence carnal reason.

Although Patrick’s tutors had urged him to accept the Bible’s teaching on predestination, the advice he received from Smith was markedly different. At his question, Patrick recalled that Smith started

laughing, and told me they were good and sound reasons which I had objected against that doctrine; and made such a representation of the nature of God to me, and of his good-will to men in Christ Jesus, as quite altered my opinion.

The rise of reason

There are at least two things that we should notice from this story. The first is that Smith was happy to reject a doctrine like predestination not on the basis of whether or not it was taught in the Bible, but human reason. One of things that the Cambridge Platonists have become famous for is the way in which they elevated human reason to such a point that they saw it as being as important, if not more important, than the Bible. Therefore, although it might seem surprising to an evangelical Christian today, it is not particularly surprising that Smith was happy to give his students the all clear to reject an important biblical concept simply because they found it unreasonable.

But what is even more instructive for us is that Smith’s use of reason seems to have stemmed from his understanding of God’s nature. In other words, how Smith approached knowing God was shaped by what he thought God was like. Similar to other Cambridge Platonists, he did not think that choosing people for salvation was the kind of behaviour that was suitable for God. In short, Smith did not think the God of predestination was worthy of worship.

Disconnected doctrine

Sometimes we can have this idea that the things we think about God are separate from other things we believe. We can even think this when it comes to other religious things. For example, what difference does our belief that God is good make to, say, what we think about the Bible? At least when we are invited to pick one up from the back of the seat in front of us and turn to page such and such on a Sunday morning. Sure, it’s nice to have these abstract ideas about what God is like. But it doesn’t always seem to make much practical difference to our faith day to day.

The problem with this way of thinking is that it doesn’t actually reflect reality. The Bible assumes that what we think about God influences everything else, not least issues such as how we can know about God. And John Smith gives us an examples of this. It’s just that, like going over the footage of the defeat of your favourite sports team, taking a look at what Smith believed shows us why things went wrong. He provides an illustration of how what we believe about God influences everything else, for good or for bad.

Bound not free

You may have got a sense of this already. In his anecdote, Simon Patrick explained that what changed his mind on predestination was the picture that John Smith painted for him of what God was like. Although we don’t know exactly what Smith said to Patrick, we do have various notes from Smith’s study which one of his friends put into a book after Smith died. And these writings show us that Smith had a rather unorthodox view of what God was like.

Smith thought that God and humanity were more alike than different, at least when it came to what they did. The Bible consistently presents God as free and independent of everything else. So, for example, in Psalm 115:3, the Psalmist famously exclaims:

Our God is in heaven;

he does whatever pleases him.

However, Smith thought that God’s actions in the world were not totally free. They were not, in Smith’s words,

the sole Results of an Absolute will, but the Sacred Decrees of Reason and Goodness.

Smith believed that God was bound by the laws of reason and goodness in how he acted in the world. And this belief not only affected what Smith thought God was like, it also influenced what he thought we are like. This is because Smith believed that God had implanted these same laws of reason and goodness in the human soul too. He wrote,

And so we come to consider that Law embosom'd in the Souls of men which ties them again to their Creatour, and this is called The Law of Nature; which indeed is nothing else but a Paraphrase or Comment upon the Nature of God as it copies forth it self in the Soul of Man.

In Smith’s mind, God’s actions were bound by the laws of reason and goodness. And Smith believed that ours are too.

Philosophical but useful

I realise that this might all sound rather philosophical. And it is. Although nearly all of the Cambridge Platonists were church ministers, they are best known today as a group of philosophers. But it would be a mistake for us to think that we can’t learn from what they thought about God, even if the lesson comes more from what they got wrong than what they got right.

This is because Smith’s mistaken beliefs about God had far reaching consequences for the rest of his theology. For not only did Smith’s doctrine of God shape what he thought we are like, it also impacted how Smith thought we could know God. As he wrote,

God having so copied forth himself into the whole life and energy of man's Soul, as that the lovely Characters of Divinity may be most easily seen and read of all men within themselves.

It is here that we see the connection between what Smith thought God was like and how Smith thought we could know him. Because Smith believed that God is more similar to us than different, he also believed that the best way of knowing God was not by looking in the Bible or anywhere else. No, God was to be found by looking inside of ourselves.

The most important thing

Those last few words seem rather familiar don’t they? The idea that you can find God by looking inside of yourself is an idea that is frequently heard from the lips of any number of academics, celebrities, and other influencers in the Western world. But did you notice where they came from for Smith? They didn't come from a secular therapy or even a different religion. They came from Smith’s view of what the Christian God was like. And that provides a sobering lesson for us.

At the beginning of his 1961 book, The Knowledge of the Holy, American theologian A W Tozer famously wrote that

What comes into our minds when we think about God is the most important thing about us.

Tozer’s point was that our view of God’s character lies at the root of our religion. This was true for John Smith nearly 400 years ago, and it is true for you and me today.

For Smith, his view of God created havoc for the rest of what he believed. Because he thought God was more similar to us than different, he neglected important topics like sin, the Bible, and Jesus in his theology. And all with the result of producing an inadequate understanding of how to know God. In short, Smith’s doctrine of God left no room for the gospel.

A key question

And so here is my question: who is God to you? Is the kind of God you believe in one of your imagination or the one revealed in the Bible?

It’s a basic question. But, if you are anything like me, it can be easy to go through life without spending much time reflecting on what God is actually like. We might go to church. We might read the Bible. We might even read Christian books and listen to faith podcast. But rarely do we dwell on the fundamental question of who God is.

And this is where Stephen Charnock can help us. Because, perhaps more than anyone else in his day, Charnock thought and wrote about the character of God. And far from being dry and dull, what Charnock put to paper was remarkably biblical, vividly illustrated, and pastorally applied.

So this summer I am going to be sharing with you some excerpts from Charnock’s reflections on the character of God. Like the series that I sent out over Christmas, they’ll be short, accessible, and come with an audio version you can listen to.

Watch out for them each week.

Thank you James. Just what I needed for a walk and talk with a brother. I look forward to summer.