The Master's Apprentice

Learning not only what to think about God but how

Don’t judge me.

One of the enduring memories from my childhood was being snuggled up on the sofa with my uncle and auntie watching The Generation Game. The staple Saturday night television show saw four teams of two people from the same family, but different generations, battle it out against each other in order to win prizes. There were music quizzes, drama performances and, of course, the final conveyor belt round where the winning team tried to remember as many items as they could in order to take them home with them.

Yet, as memorable as they were, none of those game were my favourite. That spot was reserved for the imitation round. Teams would watch a skilled professional create or perform something and then try it themselves before being given a score by the professional. Whether it was pottery or dancing, cake decorating or dog training, the hopelessness of the amateurs compared to the skill of the professional never failed to have me in stitches.

The reason that I look back on this particular game show round with such affection is because it communicated something important that I have learnt in the years since. And it’s this: the most valuable things in life require practice, and the best way to learn them is by spending time with someone who has mastered them.

It was true of the drums that I started playing at six. It was true of the map reading skills that I began working on in my teens. And, as I think about it now, it has been true of almost everything else I have learnt to do since. Driving a car. Representing a client in court. Putting up shelves. Conducting a funeral. Changing a nappy. Tutoring students training for Christian ministry. All of these are things that I have learnt from other people - listening to them, watching them, imitating them. They have been my master; I have been their apprentice.

Regular readers of this newsletter will have noticed that my updates have dried up in recent months. Whilst I cannot provide a justification, I can at least give something of an explanation. Over the last year, I have been making my way through all of Stephen Charnock’s works. With Charnock’s writings extending to around 2 million words over nearly 3,000 pages, I probably should have always realised that it was going to be a challenge to keep up my newsletter at the same time. But with that part of my PhD now in the rearview mirror, I am excited to be getting back to writing these updates again, and for the first one I thought it might be helpful to share with you something that I learnt from the process.

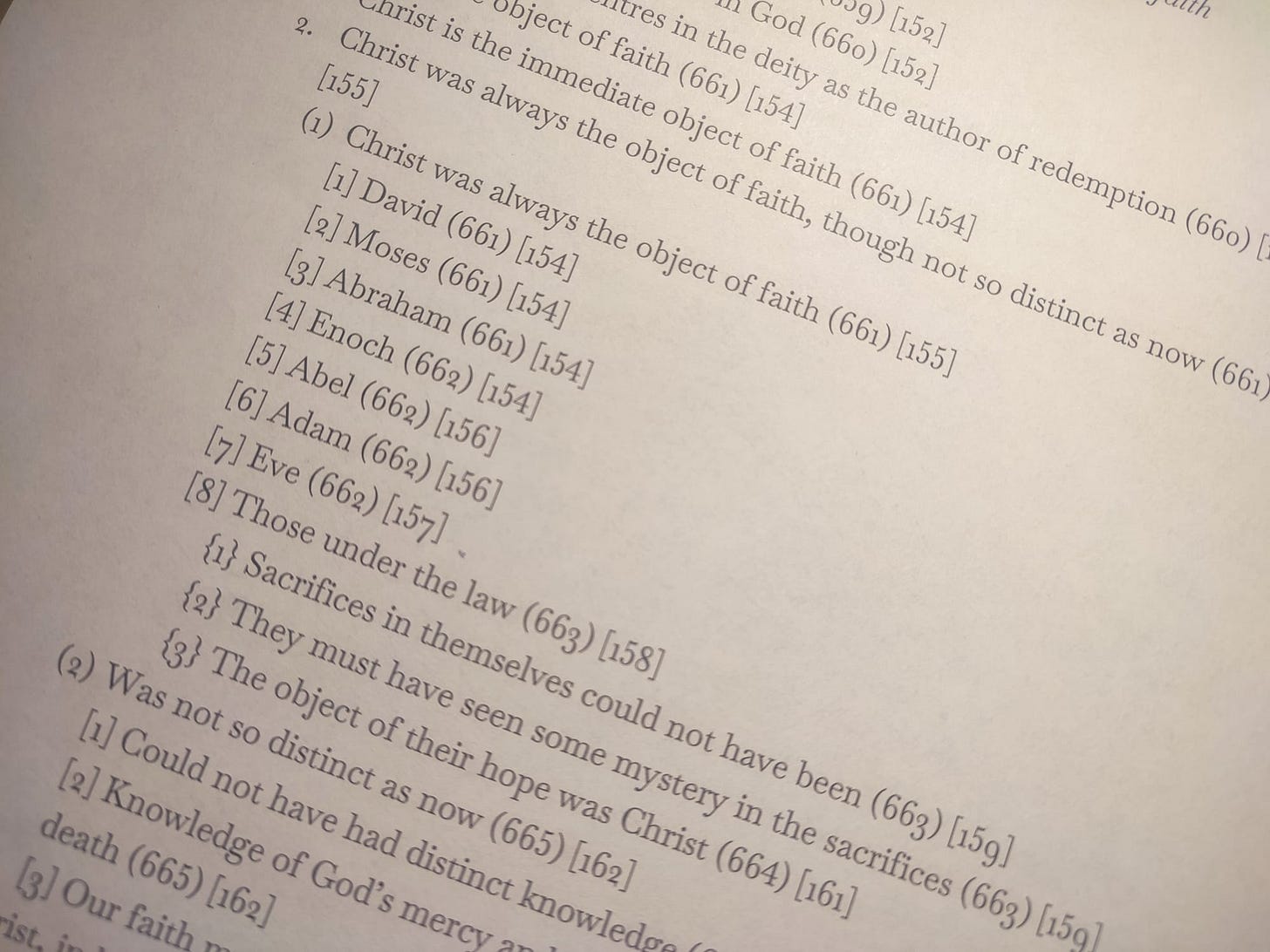

When my PhD supervisor asked me to read all of Charnock’s works, he suggested that I produce something called an ‘analytical outline’ as I went along. This is a series of one line summaries of each of Charnock’s points and subpoints, set out like a detailed contents page with bullet points and page numbers. You might have thought that adding anything on top of the large amount reading that I was already meant to be doing was going to be a distraction. Yet, that could not have been further from the truth. Producing outlines of what I was reading, transformed my interaction with what I was reading. So much so that I think it will change how I read theology from now on.

Zooming in

The first difference that the outlining made was by enhancing my understanding of what I was reading. Admittedly, working through such a large amount of material from start to finish felt overwhelming at times and I would be lying if I told you that I never felt like skipping over some of it. Summarising each of Charnock’s points within the limited scope of a single line forced me to slow down and try to understand Charnock’s argument at each stage before moving on.

Whatever our reading habits, it is good for us to engage with things that challenge us intellectually. Yet, one of the things that can put people off reading stretching theology is the fear that they will get lost in the detail. If that describes you, do not not be deterred. Instead, consider creating an outline as you go along. It doesn’t have to be as formal as the ones that I have done. It could be a note with just a word or two describing the author’s key points. Nonetheless, putting the things that we are reading into your own words can be a great way checking that we have understood what a writer is trying to say through theirs. Outlining helps us with zooming in.

Zooming out

If the outlining helped me engage with the detail of Charnock’s arguments, it also enabled me to have a clearer idea of the bigger picture of his theology. Charnock’s works are made up of 56 discourses covering a wide variety of theological subjects. Whilst some are short, many of them are long - far too long to read in one go. On top of that, there was the challenge that comes with reading old documents. For reasons that I do not need to go into now, I decided to read both the seventeenth- and nineteenth-century editions of Charnock’s works. Yet, even the more recent one was poorly formatted, at least by modern standards. Not only was the text small and fully justified, the numbering was repetitive and in some cases incorrect.

Both the length and style of Charnock’s writings make it hard, at least for a modern reader, to get a bird’s eye view of what he was trying to say. But this is where my outlining came into its own. In putting them together I was able to create something of a map to help me follow the flow of his argument. This was especially helpful when I felt that I was getting lost in a section that was complicated. By reaching for my outline, I could remind myself of where Charnock had been in his argument, and where he was headed, and this then helped me to get a better sense of what he was trying to say right now. What is more, when I came to read some more of Charnock after some time away from his books, it enabled me to quickly go back over what I had read the last time to help get me back into the flow of his thought.

In other words, outlining has proved to be helpful tool in enabling me to zoom out and keep sight of the big picture. And this is something that does not only apply to dense works of theology. Prompted by my experience with Charnock, I recently wrote up a basic outline of a few chapters from a book which my wife and I have been using in some marriage preparation sessions we are doing with a couple in our church. It took me less than 10 minutes and provided a helpful aid to our discussion.

Looking through

This bird’s eye view has helped my understanding of Charnock in one other key way. And that is by enabling me to spot key themes, emphasis, and structures across the length and breadth of his theology. Stephen Charnock was a person, and like all people, what he thought in one area impacted what he thought in another. As a result, Charnock would return to similar themes in many of his discourses. Yet, far from being repetitive, he would often develop and apply these in different ways.

To give one example, a theme which I noticed during my reading as being of particular significance for Charnock was God in Christ as the object of faith. He put this front and centre in a relatively short and little known discourse tucked away in the fifth volume of Charnock’s works called a ‘Discourse of the Object of Faith’. In the course of this sermon Charnock commented to his congregation that ‘Many will speak carelessly, and many will boast confidently, of their Faith and Trust in God, and scarce ever think or speak of Christ’. Yet, far from being limited to this discourse, this seems to have stood behind much of this theology. In particular, Charnock drew on many of the key points he developed in other parts of his writings in trying to persuade his congregation that they could not know God outside of Christ. At the same time, this concern seems to have guided how Charnock went about teaching on many other subject, even those as seemingly diverse as how we know about God, what God is like, and how God changes us. Outlining Charnock’s works has helped me to see that faith in God in Christ was a major theme, if not the major theme, of his theology.

The Master’s apprentice

As we seek to follow Jesus, our heavenly master, Christians are called to follow those who have followed in his example (1 Corinthians 11:1). This mimicking does not only include what we do, but how we think. (Because, of course, how we think shapes what we do.) As I have spent many hours working my way through the works of one person who thought deeply about God, my outlining has not only helped me in zooming in on the detail of their most complex points and zooming out to the big picture of their longest discourses, it has also helped me to look through their writings to begin to see some of the key ideas orientating his theology. As a result, they have helped me gain an understanding of not just what Charnock thought about God but how he thought about him. This, after all, is what an apprenticeship is all about - not just learning what a master craftsmen does but, more importantly, learning how they do it.

Well done! May you continue to grow in the knowledge of our God through your study of Charnock.