You can learn from anyone

Even those in other tribes

Sometimes you realise things suddenly. They come to you like a thief in the night. Before you know it, you’ve been taken hostage, unable to think in the same way again. Other times an idea dawns more slowly. Over weeks, months, and perhaps even years, it settles in your mind. An observation becomes a pattern which eventually turns into a conviction.

I have recently come to one such conviction: things are normally more complicated than we like to think.

If you’ve understood this for a while, please accept my apologies. But, looking back, I don’t think I first noticed it until Brexit. Whether it was the economic prosperity touted by the Remain Campaign or the border controls marketed by Vote Leave, both sides framed the issues around the referendum to leave the European Union as fairly straightforward. All the British public had to do was make their choice.

Yet, before the dust had settled on the ballot boxes, people started to realise that the UK’s relationship with EU was far more complex than they had previously thought. Alas, things are normally more complicated than we like to think.

Pastoral perplexity

This observation became a pattern I started noticing during my training as a pastor. Don’t worry, I wasn’t preaching politics from the pulpit. Rather, I was learning how to care for people in my church. As I spent time walking with church members in their ups and downs, I became increasingly aware that the reasons why people experienced the things they did were often more complicated than I first thought. And that went for how they responded to them too.

Of course, this wasn’t just true for the people I was trying to support. It was the case for my life too. The impatience I showed to my young children wasn’t just because of their behaviour. It may also have been caused by unfair expectations, poor behaviour management, mounting pressures at work, tiredness from a series of sleepless nights, anger that was shown to me as a child, or my desire for an easy and quiet life. In fact, my short fuse could well be influenced by all of these factors and more. Alas, things are normally more complicated than we like to think.

Charnock at Cambridge

That’s how my observations about Brexit turned into a pattern I started to notice in my pastoral work. But what has caused it to cement into a conviction are my recent efforts as a fledgling historian of the church.

This month in my studies, I have started working on a biography of Stephen Charnock. Not only will this be useful for the work I plan to do on him further down the line, it’s also serving as a gentle introduction to PhD research. As I look into the various phases of Charnock’s life, there is a clear structure for me to follow and some obvious places for me to go looking.

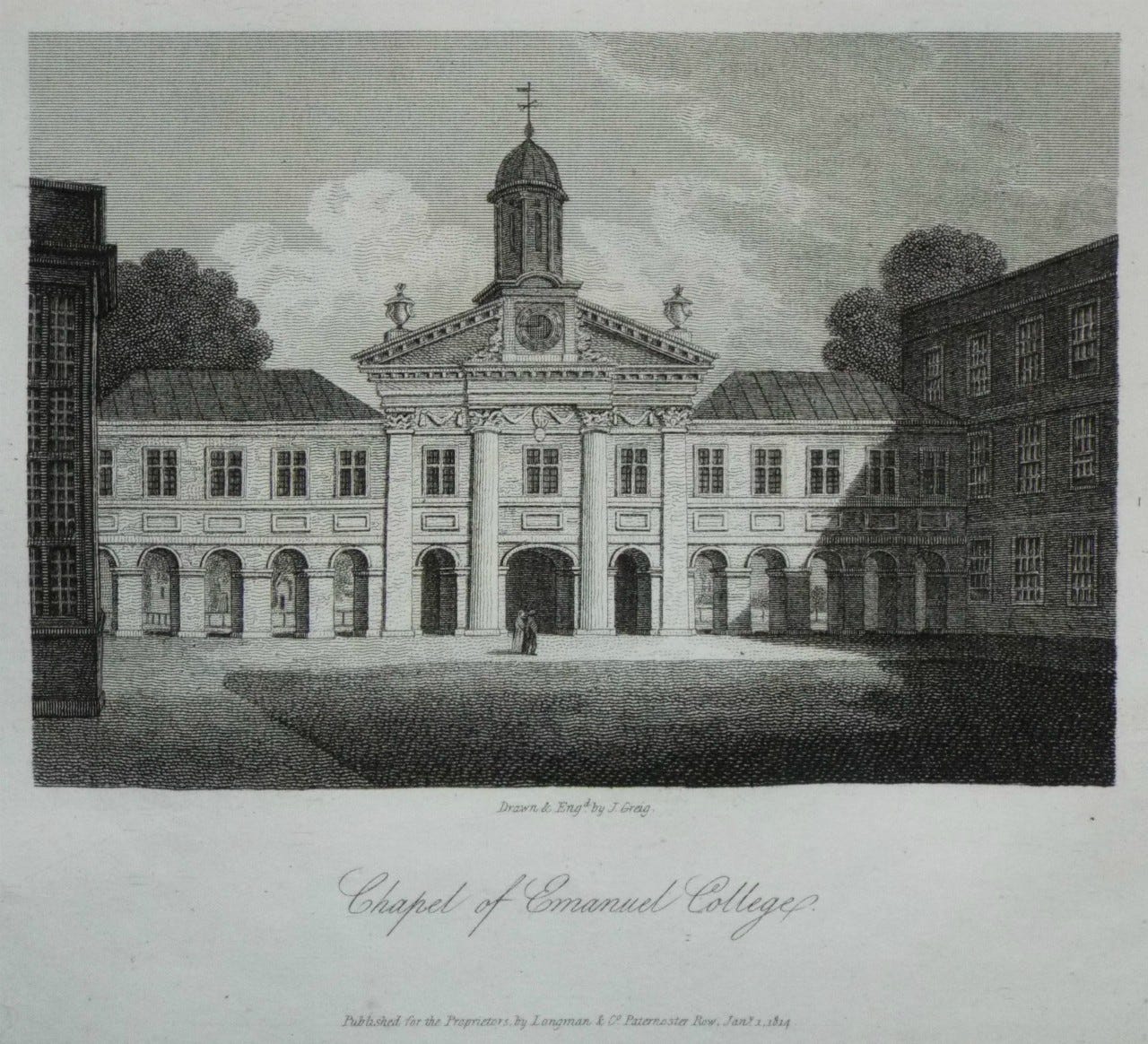

One such place is Cambridge University. At the tender age of 14, Charnock enrolled as a student at Emmanuel College. Not only was this considerably younger than the age people go to university today, but the nature of college life in the 1600s was quite different too. Charnock would have only enjoyed three hours of recreation each day and nine weeks off each year. Most of his physical, spiritual, and educational needs would have been met within the college, with his time taken up largely with reading and tutorials.

Charnock’s main tutor at Emmanuel was a man called William Sancroft, who would later become the Archbishop of Canterbury between 1678-1690. To give you an idea of what Charnock would have been studying, Sancroft gave these instructions to one of his students at Emmanuel:

First in the morning steps forth holy Hebrew in antique but grave matronlike garbe to perfume the aire … Then forth comes Seneca … within his Philosophical beesome … at last enters Horace … with his basket of flowers to deck and garnish all.

Did I mention that Charnock’s university experience was rather different to students’ today?

Right royal confrontation

But, in order to understand Charnock’s time at Cambridge, we don’t only need to know about what he studied. We also need to appreciate the religious atmosphere that would have surrounded him in college. Known as the ‘Puritan College’, Emmanuel was famous for its reputation as a hot-bed of religious nonconformity. This reputation was perhaps first started by the story of a conversation between Queen Elizabeth I and a man called Sir Walter Mildmay, who founded the college in 1588. Accused by Elizabeth with having ‘erected a puritan foundation at Cambridge’, Mildmay is supposed to have replied that he had ‘set an acorn which, when it becomes an oak, God alone knows what will be the fruit thereof.’

Whether the story is true is hard to say. However, what we can be sure of is that the college was beginning to develop a reputation for Puritanism. In what was probably the closest thing they had to an Ofsted inspection in those days, Emmanuel’s religious practices had been called out in 1604. The report complained of various ‘public disorders as touch church causes in Emmanuel College’. Instead of obeying the forms of worship in the official prayer book, it followed ‘a private course of public prayer, after their own fashion’. Ministers never wore the gowns that they were meant to wear in church worship. Nor did people kneel to receive the Lord’s Supper. Instead, they sat on forms around the communion table, passing the bread and cup from hand to hand, ‘one drinking as it were to another, like good fellows’.

By the time Charnock arrived there in 1642, Emmanuel was probably near the heights of its influence as a breeding ground for Puritanism. A significant number of the students going through the college were going on to hold important positions in the rest of society, many of whom were known for their zealous faith and their desire to worship outside of the Church of England.

Bitterer than Brexit

But it’s at this point that we must be careful not to make the mistake I mentioned earlier. Things are normally more complicated than we like to think. As a result, we should be slow in assuming that the voices that Charnock heard during his time at Emmanuel all sang from the same hymn sheet. Because, as I found out this month, the reality was far different.

I mentioned previously that Charnock’s main tutor in Cambridge was a man called William Sancroft. Well, perhaps rather surprisingly, it turns out that Sancroft was no Puritan. In fact, far from it, Sancroft was fiercely loyal to both King Charles I and the Church of England. He loved using the official prayer book and hated the plans that Parliament was making with the Presbyterians in Scotland to defeat the king and impose the Scottish system of church government in England. Describing his sadness at how the leading Anglican clergy were being treated, he wrote that they had ‘sufferd ever since buffe and steele hath swaggerd abroad in the world with soe much authority’.

Reading about these issues nearly 400 years later, it is hard for us to appreciate how controversial they were at the time. But, if you thought the UK leaving the EU was divisive, it didn’t come close to the religious and political turmoil of the 1640s. After all, that decade didn't close with a few fireworks on one side and some despondent groans on the other. It ended with the King being convicted of treason and executed before a watching crowd outside Banqueting House in London. At least Brexit hasn’t come to that.

Adolescent awakening

The atmosphere around Emmanuel College in the 1640s, full as it was with religious controversy, must have kept spiritual things on Charnock’s agenda whilst he was a teenager. Indeed, it was whilst at Cambridge that Charnock experienced his conversion. Preaching at Charnock’s funeral in 1680, his friend John Johnson described how Charnock had been without any living faith when he arrived at university. Instead,

he had been darkness, and then (he said) full of doubtings, fears, and grievously pestred with temptations.

But Charnock was then lead to search and pray. The results were remarkable,

God vouchsafed to dart such raies into his heart, as gave the light of the knowledg of the glory of God in the face of the person of Jesus Christ. So was he made light in the Lord, and believing on Christ, and God in him, filled with inward peace and comfort.

Notwithstanding the variety of voices that Charnock heard during his time at Cambridge, university had been a fruitful time for him spiritually. The wishes of Mildmay from all those years before had been fulfilled in the young man: the oak had dropped another acorn and it was fast growing into a sapling.

Culture wars

As I have been thinking about Charnock’s time at Cambridge, it has prompted me to ask whether it provides a valuable lesson for us today? Many people have observed how our cultural climate seems to have become increasingly tribal in recent years. Whether it’s Brexit, climate change or transgenderism, more and more people seem to be defining themselves by their stance on contentious issues. This can make discussion more difficult. Disagreement is no longer isolated to a particular issue, but is quickly interpreted as an attack on someone’s very identity.

Christians haven’t been immune to this. Not only has debate become fractious in general culture, it has also become more challenging within the church. Whether around seemingly more theological issues like the Trinity or more practical ones like whether churches should have kept meeting during Covid, the controversies that have arisen among evangelical Christians in recent years have sometimes felt like they have been as much about preserving party lines as speaking the truth in love. Bible scholars have demanded the resignation of scholars at other colleges. Pastors have poo-pooed all of another pastors’ writing. Church members have left congregations.

It’s not that these issues aren’t important. In fact, when it comes to something like the Trinity, the stakes couldn’t be higher for how we understand who Jesus is and what he’s done. The problem comes when we come to an issue with a tribal mentality. Because, when we tie our identity to a position on a particular issue, it makes it a lot harder for us to listen to those we disagree with, even when they are speaking about another topic all together. And the reason that we don’t want to do that is because, as I said earlier, things are normally more complicated than we like to think.

What we need

If our impatience with children can be fraught with complexity, how much more the hot button issues of our day? We need all the help we can get. For Christians, that help comes chiefly from Scripture. (I would also encourage people who aren’t Christians to consider it too). The one who ultimately wrote the Bible is also the one who made the world and everything in it.

But this doesn’t mean that we can’t get help from other places too. In fact, having Scripture as our ultimate authority frees us to learn from anyone who can help us understand it and apply it to life. This may include people who do not follow Christ but, in God’s common grace, have helpful things to say. But it certainly includes Christians who, on some issues, we might strongly disagree with.

Doing Jesus’ work

Central to Jesus’ teaching was the topsy turvy reality that whoever sees themselves as least among his followers is the greatest. One time when Jesus was teaching this to his disciples, it prompted one of them to recall a rather embarrassing incident that had happened some time before.

“Master,” said John, “we saw someone driving out demons in your name and we tried to stop him, because he is not one of us.”

It was all very well for Jesus to talk about the least of his followers being the greatest, but surely certain distinctions still needed to be made?

But this is not how their teacher replied.

“Do not stop him,” Jesus said, “for whoever is not against you is for you.” (Luke 9:49-50)

Jesus knows this man wasn’t a threat. He’d been doing Jesus’ work. And what makes this particularly poignant is the fact that, in the passage immediately before, the disciples had difficulty driving out a demon themselves. As Christians, we’re never more tempted to fall into tribalism than when we look at the ministry of others and see that it’s more fruitful than our own.

Surprising helpers

Charnock got this. Not only did he learn from a variety of voices during his time at university, he kept on benefiting from his engagement with different Christians throughout his life. The writings that we have from Charnock today are almost all based on sermons he preached at the church that he helped pastor in the City of London near the end of his life. And, in his preaching, not only did Charnock cite people from within his own camp, but he also drew on those from right across the spectrum of Christian theology. Independents, Presbyterians, Anglicans, Arminians, Socinians, Platonists, Catholics, and those associated with the ‘School of Saumur’ in France - they all got a mention in Charnock’s work. (He even referred to groundbreaking philosopher René Descartes, but that will have to wait for another newsletter.) Sure, Charnock didn’t always quote these people approvingly, but a lot of the time he did. And, where he did disagree, it was with a politeness that would probably strike many people as alien today.

Charnock knew that the issues facing Christians in his generation, like every generation, were more complicated than people often liked to think. And so Charnock was convinced that he needed to draw on the best of the Christian tradition to help the people in his church to face them.

In short, Charnock believed that God’s grace was not limited to his own tribe.

This newsletter has been long enough as it is, so I’ll keep my postscript short today.

If you would like to think a little more about how we can draw from the best of the Christian tradition, in this video Baptist pastor Gavin Ortlund talks about how Protestants can think about their relationship with traditions such as Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.

If you want to explore even further, you might enjoy this podcast interview with Michael Allen and Scott Swain. Concerned that modern evangelicals have cut themselves off from the Christian tradition, these two men have been leading voices in recent conversations about how evangelicals can start drawing from that deep well again.

You might not agree with all that is said in these recommendation. But, given the subject of this newsletter, that’s probably no bad thing.

"As Christians, we’re never more tempted to fall into tribalism than when we look at the ministry of others and see that it’s more fruitful than our own." Sadly so true. Thanks for this James.

Love this quote! “…But this doesn’t mean that we can’t get help from other places too. In fact, having Scripture as our ultimate authority frees us to learn from anyone who can help us understand it and apply it to life. This may include people who do not follow Christ but, in God’s common grace, have helpful things to say. But it certainly includes Christians who, on some issues, we might strongly disagree with.”

Encouraged by the way Charnock looked beyond his own tribe… and “…where he did disagree, it was with a politeness that would probably strike many people as alien today.”

Thanks for writing!