If you like travelling, you'll probably like church history

Why I've chosen to study historical theology

Why do you go on holiday? Maybe it’s to relax and unwind. Perhaps it’s to mark a special occasion. It might be to spend time with family and friends. There are lots of reasons to go away.

If you think about it, these are all things that you can do at home. In theory, at least. But there’s one thing you can experience on a holiday that you can never get at home. And that’s immersing yourself in another culture.

There’s something special about visiting a place for the first time. The new sights. The new sounds. The new smells. They all come together in a way which is unlike anything else we’re used to. Some things may be familiar. But other things are different. The result is often surprising. Exciting. And sometimes overwhelming.

This is especially true if you go abroad. In 2019 my wife, Helena, and I were fortunate to be able to visit a friend who was living in South Africa. Four years on, I still vividly remember the experience of meeting Beth at the airport and her driving us to the place where she was staying. Some things were familiar. The road signs in English. The billboards displaying McDonald’s latest Happy Meal. People driving on the left hand side of the road.

But so many things were different. The heat rising from the tarmac. The people begging at every traffic light we stopped at. The pop songs streaming from the car stereo in isiZulu. The security gate in front of virtually every property. The parking attendants in all of the supermarket car parks. The hoardings advertising mega church services. Some things were familiar, but many were different.

More than just dates

‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.’ That’s how L.P. Hartley opened his novel, The Go-Between.1 It’s an insightful observation. And it brilliantly summarises the valuable role that church history can play in the Christian life.

Because studying history isn’t really about learning the dates of historic events. It isn’t about reading a few choice quotes from people in the past. Rather, it’s about trying to enter the world of those people as they experienced those events. Getting a sense of the sights they would have seen, the sounds they would have heard and the smells that would have filled their nostrils. History is about trying to see things their way.2

If we want to understand people from the past in a way that they would recognise, we need to try to enter their world.

This isn’t how it has always been. Until around 10 years ago, the dominant approach in historical theology tended to look at thinkers from the past by only looking at what they said. Historical figures were largely treated as brains on sticks who operated in some sort of vacuum from the world around them. Some words from, say, Martin Luther would be taken and compared with something that someone else wrote at another time and in another place. Various lessons would be drawn, whether about Martin Luther, the other person or you and me. And that would be that.

But you don’t need to go to South Africa to realise that life doesn’t work like that. It doesn’t matter whether it’s 2019 or 1519, every person who has ever lived has done so in the midst of a whole myriad of events, people and circumstances. And here’s thing: that affects what people do. It affects what they say. It affects what they write. And, if we want to understand people from the past in a way that they would recognise, we need to try to enter their world.

Too much like hard work?

There’s an obvious objection to all of this. Reaching for a copy of Luther’s A Simple Way to Pray and reading a few lines is relatively easy. (You can read it for free at that link above, along with a whole load of other great Christian writing from the past.) But looking into what life was like for Luther in 1535, when it was first published, takes a bit more work. So you might be tempted to ask the same question I used to ask about my school homework: ‘Can’t I just do the minimum to get by?’

And you could. I am not saying that reading A Simple Way to Pray on it’s own is a bad thing to do. In fact, it will probably do you a lot of good. Nonetheless, taking even a little time to understand what was going on when it was written will only enrich your understanding of it. And it will also enrich what it can do for your soul.

Taking a test drive

So let’s try this out. How could some information about the historical context of A Simple Way to Pray enrich our experience of reading it?

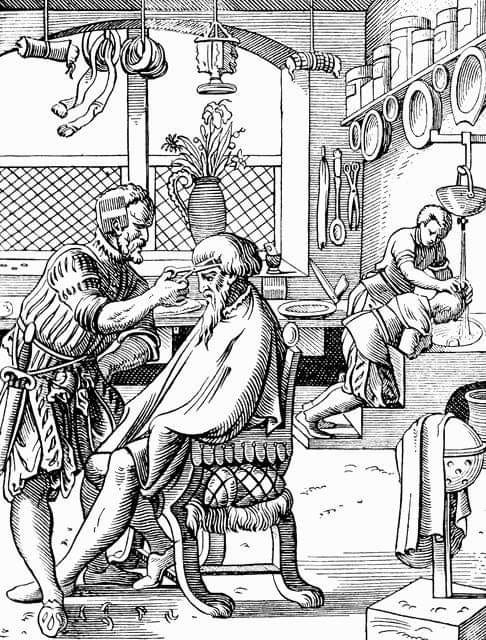

Well, imagine that you were at the hairdressers. Knowing that you’re interested in spiritual things, the person cutting your hair asks for your advice. ‘I am struggling to pray’, your hairdresser says. ‘Can you suggest something to help?’ I appreciate that this isn’t the most common question you might get asked in the hairdressers. (And certainly not not as common as whether you’ve been on holiday lately.) But novelty aside, what would you say? What advice would you offer your coiffuring friend?

That was the situation Martin Luther found himself in when he wrote a A Simple Way to Pray. Luther was visiting his good friend and barber, Peter Beskendorf. Peter had a reputation for being ‘a pious, God-fearing man who gladly listened to and discussed the word of God.’3 But on this particular occasion, Peter had a problem: he was struggling to pray. And so Peter sought the advice of his esteemed customer.

What was Luther’s response? It wasn't to offer a few clichés before running out the door. Because whatever Luther said to Peter whilst he was sitting in his barbering chair, Luther’s advice did not end there. When he got home, he started writing Peter a little book on how to pray.

Extending to just short of 20 pages, A Simple Way to Pray contains what is essentially an explanation of how Luther prayed himself. It was immediately popular and was printed four times during 1535. Altogether there were thirteen editions published during Luther’s lifetime. And it isn't hard to appreciate why. The little treatise is not only rich, but also practical. In it, Luther provides specific instruction on when, how and what to pray.

Looking at how Christians have dealt with issues in the past helps us to look afresh at how we think about things today.

Yet, even without considering the content of A Simple Way to Pray, it’s worth thinking about how remarkable it is that Luther wrote it at all. As Carl Trueman explains, ‘Luther was without doubt one of the busiest and most hard-pressed men in Electoral Saxony at the time, if not the whole of Europe, and he had a million and one more important duties pressing in on him from all sides.’ He had, for instance, recently finished his first translation of the Bible into German. He was also continuing to participate in theological debates over matters such as the Lord’s Supper. Nonetheless, Luther found time to write a letter of spiritual advice to his barber. As Trueman continues, ‘[a]ll of Luther’s learning, all of the things he had done, all of the adulation he received, all of the great and the good who called on him for advice - none of this distracted him from caring for the people in his congregation.’4

Life in technicolour

We’ve thought about only a fraction of the historical context of A Simple Way to Pray. For instance, we haven’t said anything about the way people often approached prayer in the early 16th century. Nor have we touched on the way people normally thought about things like Scripture, church and spiritual warfare, all of which feature prominently in Luther’s little prayer guide. But even the relatively small amount of background that we have mentioned adds colour to our reading of it.

Because, in those pages, Luther says some things that you don’t often hear people say today. For instance, why do people lack joy in their prayer life? For Luther, it was because of the flesh and the devil. He writes:

‘we must be careful not to break the habit of true prayer and imagine other works to be necessary which, after all, are nothing of the kind. Thus at the end we become lax and lazy, cool and listless toward prayer. The devil who besets us is not lazy or careless, and our flesh is too ready and eager to sin and is disinclined to the spirit of prayer.’

To our 21st century ears, these words might sound harsh. Maybe even a bit mean. But when we remember that they're from a loving pastor to a good friend, it changes the way we hear them. It helps us to see them not as the words of a fiery academic who stood up to the corruption of the Roman Catholic Church, but as someone who wanted to see his mate enjoy prayer again. And I dare say that this only helps us to take Luther’s words to heart too.

A tragic end

In fact, things become all the more poignant when we learn that the tale of Peter, the Master Barber, has a sobering end. Within months of Luther writing the prayer guide him, Peter’s life took a tragic turn. On the day before Easter, Peter was eating at his daughter’s house. His son-in-law, Dietrich, who had been a soldier, was apparently reporting on battles he had survived and boasting of his invulnerability to death. Peter, probably under the influence of alcohol, put this to the test and stabbed his son-in-law with his own sword at the dinner table. As it turned out, Dietrich was not as invincible as he had made out. Peter only escaped death himself because Luther managed to persuade the Elector of Saxony to banish him from Wittenberg instead of executing him.

Luther once mentioned the tragic event to friends over dinner. Who did he think was ultimately behind the awful incident? The devil.5

The re-entry

On our flight back home from South Africa, I found myself doing what I suspect many do on the return journey from a foreign culture. I started thinking. Thinking about all the sights, the sounds and the smells I had experienced over the previous three weeks. Thinking about what had been familiar, and all that had been different. And, as I re-entered British airspace, my mind ended up reflecting on how what I experienced in South Africa had changed me.

There’s nothing quite like spending time immersed in a foreign culture to help you reconsider your own. And the same is true for church history. It might be the impact that spiritual warfare has on our joy in prayer. It might be something else. Looking at how Christians have dealt with issues in the past helps us to look afresh at how we think about things today.

And that’s why I’m planning to do a PhD in historical theology.

Fancy having a go?

If I’ve whetted your appetite for doing a little church history, why not read A Simple Way to Pray? You could read it on your own or, even better, with someone else. And then talk about it together.

If you want to dip your toe in further, you could watch Luther: The Life and Legacy of the German Reformer. It’s a free and engaging documentary looking at the good (and not so good) bits of Luther’s life. I recently had some people from my church over for food and we watched it together. People enjoyed it.

Finally, to get an even fuller understanding of the man, you couldn’t do much better than read Roland Bainton’s classic biography Here I Stand: A life of Martin Luther. At over 70 years old, the book is fast becoming a bit of church history itself. But it’s worth it’s weight in gold.

I came across this quote in a series of lectures that a church historian called Carl Trueman gave when he taught at Westminster Theological Seminary in Phildelphia, USA. Sadly, I can’t remember the exact lecture in which he mentions it. In my defence, there are 33 of them!

Probably the most influential book that I have read so far in preparation for the PhD has this as it’s title. Alister Chapman, John Coffey, Brad S. Gregory (eds.), Seeing Things Their Way: Intellectual History and the Return of Religion (Notre Dame Press, 2009).

Johann G. Walch, Dr. Martin Luthers sämmtliche Schriften, 9:1822, quoted in Eric Lund’s introduction to Martin Luther, A Simple Way to Pray, ed. Eric Lund, in The Annotated Luther Volume 4: Pastoral Writings, ed. Mary Jane Haemig (Fortress, 2016), 253.

Carl R. Trueman, “A Lesson from Peter the Barber,” Themelios 34 (2009), 3-4.

Lund, Introduction to A Simple Way to Pray, 255.