A piece of jewellery. Some artwork a little person did at nursery. A pair of Levi’s you unearthed one time in a vintage clothes store. We’ve all got treasured possessions. Back in 2017, Skipton Building Society polled 2,000 Brits about their dearest items. Family photos, homes and wedding rings topped the list.

People in the past prized things too, though the items they treasured were often different to the ones we usually cherish today. That’s not surprising. Many of the things that were valuable back then, we now take for granted.

Think of books. For those that could afford them (and knew how to read them), books were treasured by people in previous centuries. That was true even after Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in 1440, and the publishing revolution it spawned over the next two hundred years. In the 1600s you couldn’t buy a book for the price you can order one on Amazon today.

Bible-loving bibliophiles

If there was a group of people who especially valued their books, it was the Puritans. As I have been doing background reading on the movement in preparation for starting my PhD, I have been inspired to invent a new game. Imaginatively called ‘Who had the biggest library?’, the aim is to try and work out who in the 17th century had the largest personal collection of books.

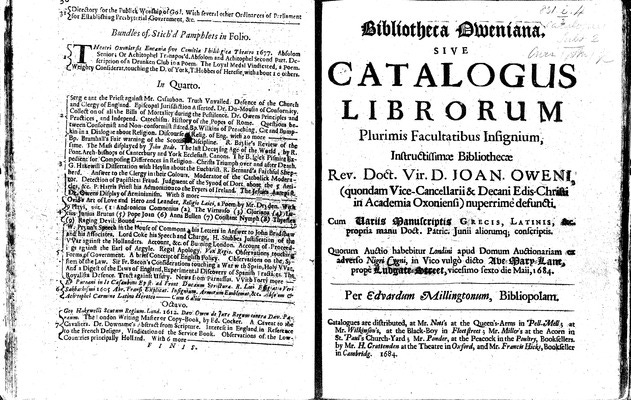

In my last newsletter, I mentioned John Owen - theological heavyweight and poster boy of Puritanism. When John Owen died in 1683 and his library was sold off, the auction catalogue recorded 3,000 volumes. (Interestingly, it seems that Owen did not own copies of all of his titles at the time of his death as the catalogue only lists a handful of the many books that Owen wrote himself.)

Yet, as sizeable as Owen’s library may have been, it had nothing on George Thomason’s. A close friend of the poet John Milton (of Paradise Lost-fame), Thomason was a committed Presbyterian who worked as a bookseller through the middle part of the 17th century. During the course of his life, he amassed a collection of pamphlets, books, and tracts. Originally said to contain more than 32,000 items, Thomason’s descendants later sold the collection to King George III, who then presented it to the British Museum. Today, the surviving ‘Thomason Collection’ numbers a mere 22,255 works in 2,008 leather volumes.

But for at least most Puritans, it wasn’t about collecting books for collecting’s sake. They worshiped a God who not only used words to create the world but to communicate his plan for saving it too. As a result, the Puritans dedicated themselves to the study of the Word and they used their libraries to help them.

A case in point

Stephen Charnock is a case in point. Over the last year, I have read the few short biographies that have been written about him. And one of the qualities that shines through is how much the old divine loved his study.

Stephen Charnock was born in 1628 in London, in the parish of St. Katharine Cree (near to where Aldgate tube station is today). At the age of 14 he was sent off to study at Emmanuel College in Cambridge. Known as the ‘Puritan College’, many of the leading figures of Puritanism were educated at Emmanuel and it’s fair to say that whilst he was there Charnock would have received a far more demanding education than you or I probably ever did. All students would have been required to study Hebrew, Greek and Latin, and become well-versed in the writings of great thinkers such as Aristotle, Plato and Aquinas.

Yet, despite all the academics, it was the gospel that made the greatest impression on Charnock whilst he was at university. Recalling Charnock’s conversion at Cambridge, a good friend by the name of Mr Johnson described it in these terms when he preached at Charnock’s funeral in 1680:

I found him one that, Jonah-like, has turned to the Lord with all his heart, all his soul, and all his might, and none like him; which did more endear him to me. How had he hid the word of God in a fertile soil, “in a good and honest heart,” which made him “flee youthful lusts,” and antidoted him against the infection of youthful vanities.

But we shouldn’t think that Charnock’s demanding education was at odds with the radical transformation that had taken place in his heart. Rather, he now dedicated all of his studies to strengthening his faith. Mr Johnson continued,

His study was his recreation; the law of God his delight. . . He was as choice, circumspect, and prudent in his election of society, as of books, to converse with; all his delight being in such as excelled in the divine art of directing, furthering, and quickening him in the way to heaven, the love of Christ and souls.

Charnock used his gifted mind to help warm both his own heart and the hearts of others.

The habit of a lifetime

Charnock’s commitment to the intense study of the Scriptures would continue for the rest of his life. After ministering in London, teaching at Oxford and serving as chaplain to Henry Cromwell in Ireland, Charnock found himself back in London and out of work. Following the Act of Uniformity in 1662, he was ejected from the Church of England, along with around 2,000 other minsters. And so with little public ministry for the next 15 years, Charnock burrowed himself away in his study, supporting himself by practising medicine on the side. (You were allowed to do that back then!)

As Charnock knew first hand, even in our greatest earthly loss, we can know God’s comforting care.

But it was during this time that Charnock suffered the loss of what was perhaps his greatest worldly possession. As you may remember from your days back in school, just after midnight on Sunday 2 September 1666, a fire started in a bakery on Pudding Lane. By Monday, the blaze had pushed north into the heart of the City of London. On Tuesday it had spread over nearly the whole area, destroying St Paul's Cathedral and leaping the River Fleet to threaten Charles II's court at Whitehall. It was not until Thursday that the fire was put out.

Whilst relatively few people died in the Great Fire of London, it damaged an enormous amount of property. In addition to St Paul’s Cathedral, the flames destroyed 13,500 houses, 87 churches, 44 Company Halls, the Royal Exchange, the Custom House, the Bridewell Palace and various other prisons, the General Letter Office, and three city gates. All in all, the damage was valued at £1.9 billion in today’s money.

One lesser known victim of the Great Fire of London was Stephen Charnock’s library. There are repeated references to the destruction of his library in an early account of his life. Whilst there is no surviving diary from Charnock (if he kept one, it was probably destroyed in the blaze), we do have the memoirs of Thomas Goodwin, who was another Puritan who lost books in the Great Fire. His son (who was also called Thomas and inherited his father’s great library) lamented the consequences of the disaster on his father's collection:

In that deplorable Calamity of the dreadful Fire at London, 1666, which laid in Ashes a considerable part of that City, he lost above half his Library, to the value of five hundred Pounds. There was this remarkable, that part of it, which was lodg’d very near the Place where the Fire began, and which he accounted irrecoverably lost, were by the good Providence of God, and the Care and Diligence of his very good and faithful Friend Mr. Moses Lowman, tho with extreme hazard, preserv’d from the Flames.

Fortunately for Goodwin, his theology books were among those that were saved. Charnock, however, was not so lucky.

Theology in technicolor

A couple of months ago, I wrote about the power of knowing a bit about a person’s history for adding colour to our enjoyment of their theology. Like an appreciation of the relationship that Martin Luther had with his barber enriches our reading of the little prayer guide that he wrote for him, knowing about the loss of Charnock’s library helps us feel the force of some of his later thinking.

By far the most famous work Charnock wrote was his Discourses Upon the Existence and Attributes of God. Published shortly after his death, it has come to be regarded by many as the finest thing the Puritans produced on the doctrine of God. However, the fame of this work has cast a long shadow over the rest of Charnock’s writings, which included reflections on subjects as varied as God's providence, the Lord’s Supper and how to comfort childbearing women. And it is the first of these writings that is particularly helped by our knowledge of the destruction of Charnock’s most treasured possession.

At 115 densely-set pages, Charnock’s discussion of God’s providence is as deep as it is wide. However, for all it's intellectual rigour, Charnock’s chapter is also profoundly pastoral. For instance, in his consideration of the comfort that comes with the belief that God directs all things, he writes,

In the greatest extremities where in his people maybe, there are promises of comfort (Isaiah 43:2). Both in overflowing waters and scorching fires he will be with them; his providence shall attend his promise, and his truth shall be their shield and buckler (Psalm 91:4).

Given his experience of the flames in the Great Fire of London, Charnock’s description of the trials of life as ‘scorching fires’ is particularly poignant. Even as Charnock searched the smoldering rubble for any surviving volumes from his beloved library, Charnock could be sure of God’s presence in his loss and pain. Why? Well, what brought Charnock most comfort was not God’s creation of everything from nothing. Nor was it His ongoing direction of those things each day. Rather, most consoling for him was the redemption of his Son. Because, in what could be some of the most heart-warming words ever written on God’s providence in the English language, Charnock continues,

He will not surely be regardless of the afflictions of his creatures. His people are not only his creatures, but his new creatures; their bodies are not only created by him, but redeemed by his Son. The purchase of the Redeemer is joined to the providence of the Creator. If he take care of you when he might have damned you for your sins, will he not much more since you are believers in Christ?

And, if that weren’t assurance enough, Charnock concludes by reminding us that God ‘cannot damn you believing, unless he renounce his Son’s mediation and his own promise.’

Treasured possessions. We’ve all got them and we can all lose them. But, as Charnock knew first hand, even in our greatest earthly loss, we can know God’s comforting care. That’s because, in Christ, we are God’s most treasured possession. And he will not - indeed, he cannot - let us go.

For those who have been following these newsletters over the last few months, you may know that recently I’ve been working on the research proposal for my PhD. Whilst I found it relatively easy to settle on Stephen Charnock for my research, deciding on which particular aspect of his thought to focus on has proven more difficult.

That being said, I am pleased to say that I finally chose the angle of my research in April, agreed the final draft of my proposal in May and had my formal application accepted in June. This means that I am all set to start my PhD with Union Theological College in Belfast in September under the supervision of Dr Martyn Cowan.

It feels like it’s been quite a journey since my boss first suggested to me the idea of me doing a PhD. I suppose that it just remains for me to get on and actually do it now. . .

Brilliant as always James- loved knowing the connection of personal history to his writings.