It’s harder to make decisions these days. That’s what it feels like, anyway. You pop into Sainsbury’s to pick up some chocolates on the way round to your friend’s house for dinner and your presented with 50 types to choose from. At the same moment, your friend opens up Spotify to select a playlist for the evening and they’re faced with four billion (yup, you read that right!). In almost every area of our lives, we face more options than ever. The problem is that it doesn’t make life easier. It actually makes it more difficult.

Psychologists call this ‘decision paralysis’. It happens when we have to choose from options that are difficult to compare. The more options we have, the harder it becomes to pick one. Whilst it certainly feels more common in our current age, it is reassuring to know that people have experienced the issue for centuries. In the ancient fable of The Fox and the Cat, the fox boasts of hundreds of ways of escaping while the cat has only one. When they hear the sound of hounds approaching, the cat scampers up a tree while the fox in his confusion was caught up by the hounds. As the fable ends, ‘better one safe way than a hundred on which you cannot reckon’.

If you asked my wife whether I am more of a fox or a cat, Helena would quickly to tell you that I have a bushy tail, not whiskers. (And it wouldn’t be a difficult decision for her because she’s more of a feline disposition.) I’ve been known to take so long selecting a film for us to watch on Netflix that Helena has given up on watching one that evening all together.

So, given my track record, how do you recon I found the experience of trying decide what to study for my PhD?

Well, it was surprisingly easy, actually. And what saved me from much dilly-dallying was one simple sentence.

My shopping list

Any savvy supermarket-shopper knows that, if you’re going to avoid the dangers of indecision, you need a list. As I started out on my search for a research topic, I wrote down my priorities.

In my first newsletter, I talked about why I believe that the most fruitful theology is done within the church. As a result, top of my list was a subject that would help me become a better pastor and that would also be helpful to my local congregation.

Last month, I posted about why church history is important. Not only am I naturally interested in it, I also believe that looking at how Christians have dealt with issues in the past can help us with things today. So, next on my agenda was something historical.

But I also needed to consider my limitations. European languages are not my strongest suit. My grade in GCSE Spanish had made that clear enough. As a result, I did not think it would be the wisest course of action to study someone who wrote mainly in, say, German or Dutch. Or, Spanish for that matter. Fortunately, as a native English speaker, there is no shortage of people who wrote their theology in my mother tongue.

Mistaken identity

These three priorities led me to focus my search in one particular aisle of the theological supermarket, that of the Puritans. It’s fair to say that the Puritans have come in for a bad rap in recent times. In the middle of the 20th century, the American satirist, H. L. Mencken, joked that Puritanism was ‘the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.’ It’s funny to many because to many it seems true. Everyone knows that the Puritans were a bunch of kill-joys, don’t they?

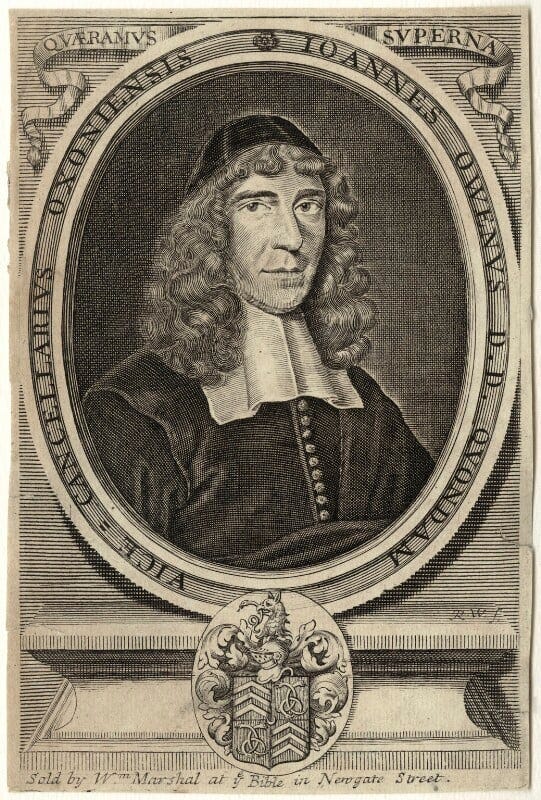

But even a little digging reveals that this notoriety is based on as much fiction as fact. To give just one example, people normally think of the Puritans as men and women who only ever wore black and only ever scowled. That is, after all, what they look like in their portraits. But, when you look at other portraits from the 17th century, you start to realise that the reason for the sombre getup probably had more to do with the fact that portraits back then were formal (and uncomfortable) things, not the temperament of the people in them.

The Puritans wore the sorts of clothes that any other person of their social status could be found wearing at the time. In fact, some were known to have been quite dapper. John Owen is commonly regarded as the greatest (and hardest to read) of all the Puritans. Apparently, the sophistication of his theology, was matched by the fashion of his dress. Owen was famous for walking through Oxford with his hair powdered, wearing a velvet jacket, in Spanish leather boots.

Head, heart and hands

Yet, reputations don’t come from nowhere. Like us all, the Puritans had their weaknesses. And perhaps their greatest flaw was a tendency to develop restrictive rules about different aspects of life, not least in relation to leisure and sports. John Bunyan, famous for writing The Pilgrim's Progress, once recalled playing a game of 'cat' on a Sunday afternoon after hearing a sermon on observing the Sabbath that morning. Between the first and second strike of the wood, Bunyan suddenly became stricken with guilt. He concluded that he was too great a sinner to be forgiven and so, in his words, 'went on in sin with great greediness of mind.'

For the Puritans, all of life was God’s and that meant that God was relevant to all of life.

But the source of their greatest weakness was also the source of their greatest strength. These ‘hotter sort of Protestants’ of the 17th century had a big view of God. Moreover, they allowed that to shape all of life. Yes, that led some of the Puritans towards legalism at times. However, it also ensured that their theology never remained abstract. John Owen claimed that ‘our happiness consisteth not in the knowing the things of the gospel, but in the doing of them.' The deep thoughts that the Puritans had about God in their heads flowed out through their hearts and into their hands.

For the Puritans, all of life was God’s and that meant that God was relevant to all of life. Work, marriage, sex, money, family, education, society - no area was off-limits to the transforming power of the gospel. This led them to adopt remarkably progressive views on a whole of range of issues, by the standards of the time. The attitude of the Puritans towards women is one example. Much writing in the early church saw women as snares to men. These attacks continued into the Middle Ages. However, the Puritans treasured women, seeing them as of equal value to men. Of course, this was not part of a political agenda. It was the result of their understanding of God’s design as revealed in Scripture. Although often overlooked, today we still enjoy the legacy of the Puritans’ attitude towards a whole range of issues.

The biggest book I could find

This combination of deep theology and practical application first came onto my radar from studying the Puritans as part of my course with Crosslands. And, over the last 60 years or so, many others have discovered it too. Since the late 1950s, there has been a growing interest in the Puritans. In fact, the enthusiasm has been so strong that it has led to the reprinting of close to 1,000 Puritan volumes in the years since, not to mention the publication of scores of new books on the movement as well. This has undoubtedly been a great blessing to the church. However, for my present deliberations, it did attend a challenge.

Of all the people, issues and ideas associated with the Puritans, which one should I focus on for my PhD? Mindful of how difficult I find it choosing a film on Netflix, it’s fair to say that this question filled me with no small amount of trepidation. So, it was with a deep breadth that I opened the largest book I could find on Puritan theology in the hope of getting some inspiration.

Running to over 1,000 large, densely-set pages, A Puritan Theology by Joel Beeke and Mark Jones has been described as the magnum opus of the recent renaissance in Puritan studies. Over the course of 60 chapters, the authors discuss what the Puritans thought on all the key areas of theology. It’s a big book!

So, after lugging it to my desk, I spent a couple of minutes scanning the contents pages, looking for any headings that piqued my interest. I spotted one on God’s attributes, which I had done some dedicated reading on a couple of summers ago. ‘Stephen Charnock on the Attributes of God’ was the name of the chapter. And, as I turned to it, I had little idea that what I was about to read would change the rest of my life.

On the scent

The first sentence of the chapter said this:

Very little work on Stephen Charnock (1628–1680) exists in the secondary literature.

Well, this was a promising start. I knew that one of the criteria for a PhD is that you need to provide a unique contribution to scholarship. So I figured that, if not much study had been done on this Charnock guy, he might be a good person to look at.

I kept reading:

Those who have heard of him tend to know of his magnum opus, Discourses upon the Existence and Attributes of God. No doubt the sheer size of the volume has caused not a few persons to direct their reading efforts elsewhere. This is regrettable for a number of reasons, not the least of which is Charnock’s ability to combine rigorous theological discourse on the doctrine of God with the typical Puritan emphasis on “uses” of the doctrine (relating doctrine and life). His work has much value on a practical level, which should be the goal of all theology.

Having read that, my heart was now beginning to race. Not only had little work been done on this man, but he also appeared to have been a prime example of what had drawn me to the Puritans in the first place. I read the rest of the chapter. I then hopped onto the internet to see what else I could find about Stephen Charnock. I was like a dog who had just caught the first whiff of a scent. Excitedly, I searched online bookshops, journals and academic libraries for anything that had been written on him. The next few hours passed by in what seemed like a few minutes. But all I had to show at the end of my scurry of activity was a handful of monographs and no more than a dozen chapters and articles of varying lengths. What Beeke and Jones had written 10 years previously was still true today: very little work on Stephen Charnock existed in the secondary literature.

Meeting Stephen Charnock

Even with the little I knew, I could see how remarkable this was. In one of those articles I had found online, someone had written,

In a word, for weight of matter, for energy of thought, for copiousness of improving reflection, for grandeur and force of illustration, and for accuracy and felicitousness of expression, Charnock is equalled by few, and surpassed by none of the writers of the age to which he belonged.

Charnock, it seemed then, was one of the heavyweights of Puritanism. But not only were his reflections profound, they also covered vast areas of theology. Charnock is best known for his work on God’s attributes. However, he also wrote some great stuff on Christ, salvation, the church and a whole load of practical issues as well. And the more I read of him, the more I knew that I wanted to study him for my PhD. The decision was made.

Yet, one problem still remained. And it was this: because Charnock wrote so widely, I wasn’t going to be able to look at all of his theology for my PhD. No, I was still going to need to decide exactly what aspect of Charnock's theology I wanted to focus on.

And so it would turn out that my decision wasn’t going be so easy after all. But that’s for another newsletter.

Want to find out more?

In the meantime, if you would like to find out more about the Puritans, why not have a look at some of the great resources out there designed to help people see what made them so special?

Following God Fully: An Introduction to the Puritans is the best general introduction I have come across. As well as telling you about some of the movement’s key characters, Joel Beeke and Michael Reeves also unpack what made the Puritans tick.

If you’re interested in going beyond the myths and legends to get a sense of the Puritans as they really were, I’d recommend you get your hands on a copy of a book by the same name. It’s called Worldly Saints: The Puritans As They Really Were. From money to family to education, Leland Ryken does a great of looking at how the Puritans approached a whole range of issues, warts and all.

But you couldn’t do better than read some of the Puritans yourself. A lot of what the most famous Puritans wrote is available for free online at Digital Puritan Press. If you’re not sure where to start, take a look at this video below where two lovers of the Puritans share some their personal recommendations. They really know their stuff!