I had lots of heroes when I was a child. There was England footballer Paul Ince. Brazilian skateboarder Bob Burnquist. Oh, and I shouldn’t forget American drummer Chad Smith from the Red Hot Chili Peppers. But like many boys, the top spot wasn’t taken by someone famous. It was reserved for my dad.

It’s hard to say what clinched it. My father’s Saturday night curries were legendary in our family, and so too were the pieces of furniture that he made in the woodworking shed. But as I look back now, the fondness that I had for my father wasn’t caused by any one thing. Rather, it was the result of the myriad of interactions that made up our relationship. To me, Dad was just the bee's knees.

But something happened in my teenage years. The bubble burst.

I still remember the evening that I saw my father’s flaws like I had never done so before. I still remember the argument we had around the kitchen table. And I still remember trying to make sense of the new reality amidst my tears. Like an old injury, the memory still makes me wince, even though it happened over 15 years ago.

Out of touch

Now don’t get me wrong, I still look up to my dad. He is an example to me in so many ways. It’s just that I now relate to my dad with an appreciation of his weaknesses as well his strengths. I suspect that this isn’t unusual. In fact, learning to see the foibles of those you look up to may just be a natural part of growing up. But, whilst it might be normal with people we know well, it seems much rarer when it comes to those further away.

Whether it’s Taylor Swift or Nigel Farage, Marcus Rashford or J K Rowling, we tend to go all in with either adoration or criticism for our more famous idols. In last month’s newsletter I noted our culture’s tendency to write off what people say on any issue when we disagree with them on one in particular. But the inverse is also true: we accept what someone says on every issue because we agree with them on one especially. In our assessments of our society’s biggest influencers, there seems to be little room for nuance, for subtlety, for complexity. In other words, we struggle with reality.

A bright cookie

But before we start bemoaning the present day, it's worth acknowledging that things have often been this way. That's not to say that there aren't any novel quirks to our current cultural climate. However, the propensity to paint our heroes in so flattering a light that we blind ourselves to their flaws is something people have experienced for centuries. And it might surprise you to know that one group that has been particularly vulnerable to this is Christians.

The first task of my PhD has been to research and write a chapter-length biography of Stephen Charnock. The last time someone wrote an account in this level of detail was over 150 years ago, and the man who did it was called James McCosh. Having first worked as a church minister, McCosh went on to become professor of philosophy at what is now Queen’s University in Belfast and then president of what is now Princeton University in America. This is all to say that McCosh was a bright cookie, well used to thinking critically about some of life’s most difficult questions. Indeed, so celebrated was his work that a lecture in religious studies is given each year in his name at Queen’s University.

As I have read the various accounts of Charnock’s life, it has struck me how flattering many of them are. Perhaps this is not surprising in respect of the accounts written by Charnock’s friends. But given McCosh’s academic pedigree, we might think that his biography would be a little more like real life. Yet, in fact, it seems more guilty of favouritism than most. And nowhere can you see this seen more clearly than in how McCosh talks about the most dramatic event of Charnock’s years.

Castle conspiracy

In 1660 Charnock returned to England after working as one of Henry Cromwell's chaplains in Ireland. With the death of his father, Oliver, in 1658, Henry’s rule in Ireland quickly broke down and two years later Charnock found himself back home in London and without a job. With the re-establishment of the monarchy under Charles II, and the persecution that people like Charnock experienced because they didn’t want to worship within the Church of England, Charnock’s unemployment would continue for a decade and a half.

Although the records we have surrounding this period in Charnock’s life are few and far between, we haven’t been left without any documentation. In fact, the majority of evidence that does exist implicates Charnock in a plot to overthrow the Irish government. In April 1663 the government received a report from one of it’s undercover agents that conspirators were planning to launch an insurrection from Dublin Castle and that Charnock had returned to Ireland to help them. A few weeks later, the authorities received another report about Charnock, this time from another source. Thus, Charnock now found himself at the centre of the government’s gaze. But instead of jumping in there and then, the authorities decided to bide their time. As one of the administrators explained to the king, to act hastily would risk letting the conspirators escape the death penalty and live to scheme again.

Culinary camouflage

So plans were allowed to continue apace over the following weeks. On the morning of 20 May, the government received full details of the plot from one their spies. There were supposedly 1,000 horsemen in Dublin who would secure the castle. Once taken, 16,000 soldiers from other parts of the country were to join the rebellion. Key members of the government would be seized. Six ministers had even been assigned the task of patrolling the streets of Dublin, ensuring that no looting was carried out.

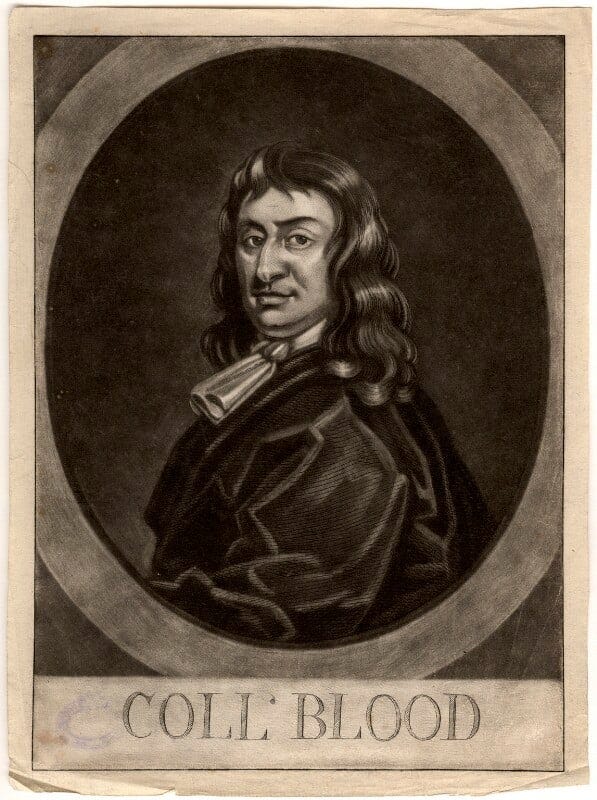

Whilst its scale may have have been exaggerated, the conspiracy itself was not. Later on 20 May three congregations met to pray for the scheme. That night the leader of the plot, a man called Colonel Thomas Blood, had dinner at a nearby pub with other key organisers in order to go over the last minute details. Around 6am the following morning, six rebels would enter the great gate of the castle in disguise. As they moved towards the fortress’ back entrance, a band of around 100 soldiers would take up positions outside the gate. On a signal, another rebel would arrive at the back of the castle disguised as a baker. He would spill loaves of bread as he entered the gate, enabling the six rebels in disguises to jump the distracted guards and allow the solders to pour into the castle. Whist they secured the castle gates, the men on horseback would move through the city, breaking up any groups of government soldiers and securing the city gates. After securing Dublin, the soldiers planned to march north to join forces with the Scots in Ulster.

No matter how well planned the plot may have been, it was not to be. With the intelligence from their undercover sources, the government increased the security presence at the castle. Discussing their plans in the pub on the evening of 20 May, Blood and others realised that, if they were going to pull the scheme off, they were going to need more firepower. The group decided to hold off to give time for an additional 500 men to arrive in Dublin over the next week.

On the run

Hearing in the early hours of 21 May that the uprising had been delayed, the government finally pounced. They dispatched parties to arrest the conspirators. Two dozen were initially taken, including six ex-officers, four of whom had served under Henry Cromwell. By mid-June the number in custody had risen to 70. Yet, Charnock was not among their number.

In order to obtain the evidence needed to capture and prosecute the key perpetrators, the government pardoned some of their prisoners in exchange for confessions. According to the evidence of someone called James Tanner, he had been recruited in early April 1663 after Blood showed him a letter from Charnock. He also confessed that Charnock had arrived in Dublin from England around 1 April, where he had been present at a meeting with Blood for the planning of the plot.

With this evidence in hand, the government issued a warrant for Charnock's arrest. It investigated a report that he was lodging with a stationer called Thomas Littlebury in London. However, Charnock took efforts to disguise his whereabouts by marking his correspondence with a ‘C’ and changing his surname to ‘Clark’. He was never arrested.

Guilty verdict

As I mentioned before, not all of Charnock’s previous biographers have accepted his involvement in Blood’s plot. Some didn’t mention it all, whilst others like McCosh disputed it as a ‘scandalous story’. But, as the saying goes, there is no smoke without fire. And, in Charnock’s case, there seems to have been rather a lot of smoke.

Not only is there the evidence of a number of primary sources, but also a motive and opportunity. Charnock, like the vast majority of others implicated in the plot, had been close to Henry whilst he ruled in Ireland and may have dreamt of him returning to rule. Given the close ties that most of the conspirators had with Henry, it is not unlikely that Charnock had connections with them prior to his return to England. In fact, there is documentary evidence to suggest that Charnock had already returned to Ireland on at least one occasion by the end of 1661. McCosh even recognised this, admitting that

We can readily believe that Charnock should deeply sympathise with the grievance of his old friends in Dublin.

Nevertheless, McCosh went on to insist on Charnock’s innocence. He concluded that

His sober judgment, his peaceable disposition, his retiring and studious habits, all make it very unlikely that he should have taken any active part in so ill-conceived and foolish a conspiracy.

Letting the cat out of the bag

I don’t know about you, but to me that final remark reveals more about McCosh than Charnock. For whilst Charnock does seem to have had some the characteristics which McCosh describes, that does not mean that Charnock could not have been involved in a conspiracy. People, after all, are complex beings and full of all sorts of flaws and contradictions. Indeed, Charnock himself recognised this more than most.

In one of his shortest works, Charnock described the power of sin to distort how we see ourselves. He wrote,

It is natural to man to think well of himself, and suffer his affections to bemist or bridle his judgment. A biassed person cannot be a just judge. Every man is his own flatterer, and so conceals himself from himself.

Charnock gives the sobering example of King David after he went to bed with Bathsheba and tried to cover it up by ordering the murder of her husband, Uriah (2 Samuel 11). Charnock remarked that David

so loved himself that he saw nothing of his sin, but was fair in his own eyes till Nathan roused him up by telling him, ‘Thou art the man’.

But, given Charnock’s involvement in the scheme to overthrow the Irish government, those words aren’t the most salient in Charnock’s short discourse. That prize should probably be saved for what he said next. For in describing just how seriously our sin can impair our judgment, he said

This self-love may so far bemist a good man, that he may not believe such an act to be a crime, such an excuse to be a fig leaf, such a mark to be unsound.

In light of the questionable legality of his involvement in Blood’s plot, Charnock’s words are rather poignant.

A doctor for the sick

No doubt, if Charnock were here today, he would try and justify his actions in one way or another. But perhaps that only strengthens the point further. Even the most mature Christians can sometimes see themselves through a distorted frame. And, as McCosh shows, mature Christians can also compound the problem by viewing other Christians with rose-tinted spectacles.

At this point we might be tempted to despair. If sin effects us so deeply that it can distort how we view ourselves, not to mention how we view someone else, what hope is there for how we view the most important questions in life. Well, this is where Charnock gives us perhaps his most helpful advice:

In case we find ourselves not in such a condition as we desire, let us exercise direct acts of faith. Let us not deject ourselves … but let us cast ourselves upon the truth and faithfulness of God in the promise of life in Christ.

Like so often in the Christian life, it is only as we see ourselves as we truly are that we can experience God’s grace as it truly is. As Charnock went on to say near the close of his discourse,

When we can find no grace to present Christ with, we should fetch grace from him. A city of refuge is for a malefactor, a physician for the sick, and a Christ for those that groan under the burden of sin ; a Christ lifted up and dying, for those that are stung by the serpent.

I hope you have enjoyed this month’s newsletter. If you know of anyone who you think might enjoy it, please do share it with them and encourage them to subscribe.

If you would like to delve a little deeper into the subject of today’s installment, you couldn’t do any better than read Charnock’s A Discourse of Self-Examination. At only 11 pages, it is one of the shortest of Charnock’s writings. Full of wonderful theology and lively language, the discourse will give you a taste of why I have chosen Charnock as the subject of my PhD. You can download a copy of the discourse at the link above.

Thank you for this interesting and encouraging article James. I enjoyed listening to it.

Thank you for sharing. I thoroughly enjoyed reading this.